Table of Content

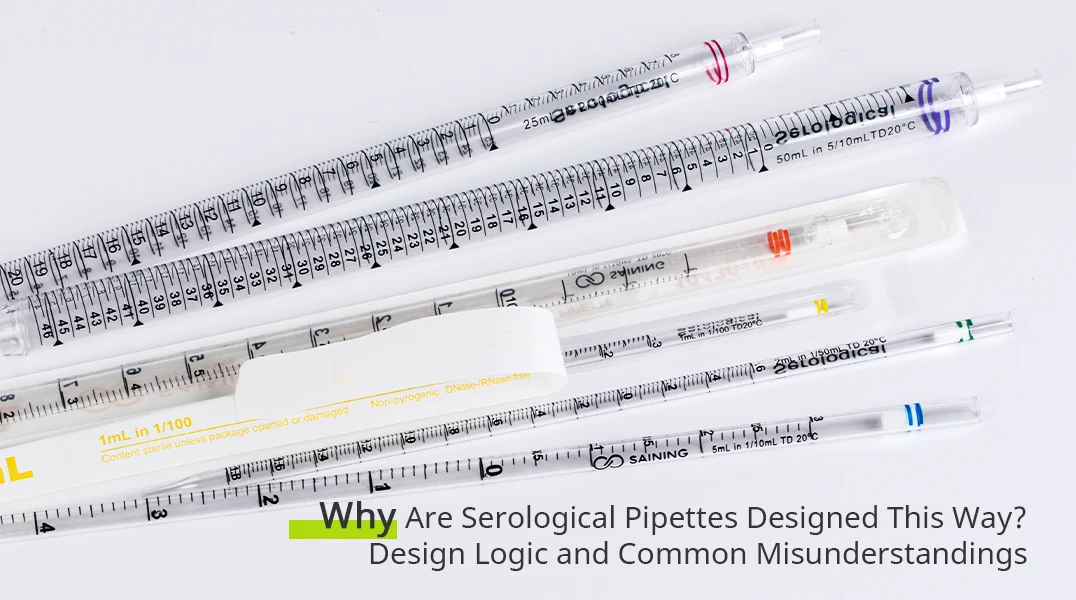

Serological pipettes are part of everyday life in many laboratories. Whether transferring culture media, handling large liquid volumes, or supporting routine cell culture work, they are often picked up almost without thinking. Their shape, length, color coding, and the way they are used feel familiar enough that few people stop to question them.

But have you ever wondered why serological pipettes are designed so differently from other types of pipettes? Why they are long, disposable, color-coded, and often require a blow-out step? These features are not arbitrary. They reflect specific design decisions shaped by laboratory workflows, human factors, and practical constraints—decisions that also give rise to many common misunderstandings.

This article takes a closer look at the design logic behind serological pipettes and clarifies some of the most frequently overlooked details in their everyday use.

Why Serological Pipettes Are Designed the Way They Are

At first glance, the design of a serological pipette seems straightforward: a long, straight tube with graduations along the side. In practice, however, nearly every aspect of its design reflects a deliberate response to how liquids are handled in real laboratory workflows. Unlike precision pipettes that prioritize microliter-level accuracy, serological pipettes are built to support repetitive, larger-volume transfers where consistency, speed, and ease of handling matter just as much as nominal accuracy.

Why Serological Pipettes Are Disposable

The disposable nature of serological pipettes is often taken for granted, but it is not merely a matter of convenience. In many laboratory settings—especially cell culture and microbiology—liquid transfer is frequent, repetitive, and closely tied to contamination risk. Reusable glass pipettes once dominated these workflows, but they required washing, drying, sterilization, and careful handling to avoid cross-contamination. Each of those steps introduced variability, both in cleanliness and in turnaround time.

Disposable serological pipettes reduce this variability by removing cleaning and reprocessing from the equation altogether. More importantly, they standardize the starting condition of each transfer: a fresh, unused surface with predictable wetting behavior. For experiments that rely on consistent handling rather than absolute volumetric precision, this consistency can be more valuable than the theoretical accuracy of a reusable alternative.

Why Most Serological Pipettes Are Plastic, Not Glass

The widespread use of plastic—most commonly polystyrene—often raises questions among researchers accustomed to thinking of glass as the more “inert” material. In the context of serological pipettes, however, material choice is closely tied to workflow demands rather than chemical idealism. Plastic pipettes are lightweight, resistant to breakage, and compatible with high-throughput environments where pipettes are frequently discarded after a single use.

From a practical standpoint, plastic also allows manufacturers to control dimensions, graduations, and surface characteristics at scale. This uniformity supports predictable liquid behavior across batches, which is critical when multiple users handle liquids in parallel. While material interactions can matter for certain sensitive applications, in routine liquid transfer the reliability and safety of plastic often outweigh the benefits of glass.

The Logic Behind the Standard Color Coding System

Walk into almost any laboratory, and serological pipettes from different brands will look strikingly similar. The same volumes are associated with the same colors, regardless of manufacturer. This consistency is so common that it often goes unnoticed. Yet the color coding system used for serological pipettes is not decorative, nor is it a branding choice—it is a practical solution to very real problems in laboratory workflows.

Color Coding as a Lab Efficiency Tool, Not a Branding Choice

The primary purpose of color coding is to allow rapid visual identification of pipette volume. In busy laboratory environments, researchers frequently work with multiple pipettes at once, often while wearing gloves and focusing their attention on samples rather than labels. Color provides an immediate, low-effort cue that reduces the need to read fine graduation marks or printed text.

Over time, these colors became standardized across the industry. This standardization is especially important in shared labs, teaching environments, and multi-user facilities, where pipettes from different suppliers may be used interchangeably. A consistent color-to-volume relationship reduces hesitation and cognitive load, allowing researchers to move fluidly through routine tasks without unnecessary interruptions.

How Color Coding Reduces Errors in High-Throughput Lab Work

In high-throughput or time-sensitive workflows, small interruptions can lead to mistakes. Picking up the wrong pipette volume is a surprisingly common source of error, particularly when multiple steps are performed repeatedly. Color coding acts as a secondary verification system—one that operates even when attention is divided.

This is particularly valuable in environments where multiple researchers work side by side, or where new lab members are still becoming familiar with equipment. Instead of relying solely on experience or careful label reading, the color system provides a shared visual language. It helps prevent volume mismatches before liquid is ever aspirated, which is far easier than correcting an error after the fact.

Common Misconceptions About Color and Accuracy

A common misunderstanding is that color coding implies differences in accuracy or performance. In reality, the color itself has no direct relationship to volumetric precision. Two serological pipettes of the same nominal volume but different brands may share the same color, yet still differ slightly in graduation quality or manufacturing tolerance.

Color coding serves identification, not measurement. Accuracy is influenced by factors such as graduation clarity, manufacturing consistency, liquid properties, and user technique. Confusing visual identification with performance can lead to misplaced confidence—or unnecessary doubt. Understanding the intended role of color coding helps set realistic expectations and keeps attention focused on the variables that truly matter.

Blow-Out Pipettes: What the Design Is Trying to Achieve

Among the many design features of serological pipettes, the blow-out function is one of the most frequently misunderstood. Many researchers learn to “blow out” simply because it is written on the pipette or taught during training, without fully understanding what problem this step is meant to solve. As a result, it is sometimes treated as either absolutely essential—or completely ignored—depending on habit rather than intention.

Why Blow-Out Pipettes Exist in the First Place

The blow-out design addresses a fundamental reality of liquid transfer: not all liquid leaves the pipette naturally under gravity. A small amount of liquid tends to remain on the inner wall of the pipette due to surface tension, especially when transferring aqueous solutions. By extending the graduation marks to the very tip and allowing an air push at the end, blow-out pipettes aim to deliver the full measured volume more consistently.

This design choice reflects a compromise. Rather than attempting to eliminate liquid retention entirely—which would require more complex materials or coatings—the blow-out step provides a simple, user-controlled way to reduce variability. It assumes active participation by the user and integrates that action into the volume measurement itself.

When the Blow-Out Step Matters in Real Experiments

The importance of the blow-out step depends heavily on context. In applications where approximate volume transfer is sufficient, the difference made by blowing out may be negligible. In contrast, when handling media preparation, reagent mixing, or cell culture workflows that rely on consistent volume ratios, skipping the blow-out step can introduce subtle but cumulative discrepancies.

It is also worth noting that overemphasis on blow-out can sometimes lead to its own issues. Excessive force or inconsistent timing may introduce bubbles or splashing, particularly at the receiving vessel. Understanding when blow-out contributes meaningfully—and when it does not—allows researchers to apply the technique deliberately rather than mechanically.

Blow-Out vs Non–Blow-Out: A Practical Perspective

In everyday lab work, the distinction between blow-out and non–blow-out pipettes is less about right or wrong and more about workflow alignment. Blow-out pipettes are designed with the assumption that users will actively complete the transfer. Non–blow-out designs, by contrast, rely on passive delivery and are better suited to applications where residual liquid is expected and accounted for.

Problems arise when these assumptions are mismatched with practice—using a blow-out pipette without blowing out, or treating a non–blow-out pipette as if it were designed for full delivery. Recognizing the intent behind the design helps avoid these mismatches and improves consistency across users.

Why Blow-Out Is Often Over-Taught and Under-Explained

In many labs, blow-out becomes a rule rather than a concept. New researchers are told what to do, but not why they are doing it. Over time, this creates rigid habits that may not always align with the experimental goal. The result is confusion: some researchers insist on blow-out in every situation, while others dismiss it entirely.

A clearer understanding of the design logic behind blow-out pipettes helps bridge this gap. It reframes the technique as a tool—one that can be applied thoughtfully rather than automatically—and encourages users to focus on consistency and intent rather than ritual.

Subtle Technique Factors That Affect Volume Accuracy

Even when using the same serological pipette, differences in technique can lead to noticeably different outcomes. These variations are often subtle enough to go unnoticed during routine work, yet significant enough to affect consistency over time. Understanding how technique interacts with pipette design helps explain why results may vary between users—or even between repeated runs by the same person.

Aspiration Speed and Liquid Behavior

Aspiration speed plays a larger role than many researchers realize. Drawing liquid too quickly can introduce turbulence, bubbles, or uneven wetting of the inner wall. These effects may not be obvious at first glance, but they change how liquid behaves during dispensing and can lead to small but systematic volume loss.

Slower, more controlled aspiration allows liquid to rise smoothly and coat the inner surface more uniformly. This reduces bubble formation and improves the predictability of the subsequent dispense. Importantly, the goal is not to move slowly for its own sake, but to maintain consistency from one transfer to the next.

Angle, Meniscus, and Reading Consistency

Reading the graduation on a serological pipette seems straightforward, yet small differences in viewing angle can lead to inconsistent interpretation of the meniscus. When the pipette is tilted or viewed from above or below the correct line of sight, the apparent liquid level can shift, especially with larger volumes.

Consistency matters more than perfection. Using the same angle, eye level, and lighting conditions helps minimize variation between readings. This is particularly important in shared laboratories, where different users may have different habits. Aligning on a common approach can improve reproducibility without changing equipment.

Controller Handling: An Overlooked Variable

The pipette controller is often treated as a neutral accessory, but it plays an active role in liquid handling. Differences in trigger sensitivity, airflow control, and user grip can influence both aspiration and dispensing behavior. Even with the same controller, variations in hand pressure and timing can lead to inconsistent results.

Experienced researchers often develop an intuitive feel for their controller, adjusting speed and pressure subconsciously. Problems arise when controllers are shared or swapped without recalibration of technique. Recognizing the controller as part of the system—not just a holder for the pipette—helps explain why identical setups can still produce different outcomes.

Common Lab Myths About Serological Pipettes

Serological pipettes are among the most familiar tools in the lab, which makes them particularly prone to assumptions. Over time, habits become rules, and rules turn into “truths” that are rarely questioned. Many of these beliefs are not entirely wrong—but they are often incomplete. Clarifying them helps reduce unnecessary variation and improves consistency across users.

“All Serological Pipettes Perform the Same”

Because serological pipettes are designed for routine liquid transfer, it is easy to assume that differences between brands or batches are negligible. In practice, subtle variations in graduation clarity, inner surface finish, and dimensional consistency can influence how liquid behaves during aspiration and dispensing.

These differences rarely cause dramatic failures, which is why the myth persists. Instead, they show up as small, cumulative inconsistencies—slightly different meniscus behavior, variable liquid retention, or changes in how much force is needed during blow-out. For individual transfers, this may not matter. Over repeated workflows or across multiple users, however, these differences can become noticeable.

“Blow-Out Always Improves Accuracy”

The blow-out step is often taught as an absolute rule, leading to the belief that blowing out always results in better accuracy. In reality, blow-out is a design feature intended to reduce variability under specific conditions—not a universal correction mechanism.

In some workflows, blowing out ensures more complete delivery of the measured volume. In others, especially when force or timing is inconsistent, it can introduce bubbles or splashing that offset its intended benefit. Treating blow-out as a context-dependent tool rather than a mandatory step helps align technique with experimental goals.

“If It’s Sterile, Contamination Isn’t a Concern”

Sterility labels can create a false sense of security. While sterile serological pipettes reduce the introduction of external contaminants, they do not control what happens during handling. Touch points, exposure time, airflow, and workflow design all influence contamination risk.

This myth often leads to relaxed technique rather than improved outcomes. Experienced researchers tend to manage these risks intuitively, while newer users may overestimate the protection provided by sterility alone. Recognizing sterility as a baseline condition—not an active shield—helps maintain appropriate vigilance without unnecessary anxiety.

“Volume Errors Are Always Caused by Poor Technique”

When volume discrepancies appear, technique is often blamed first—and sometimes rightly so. However, this assumption can obscure other contributing factors. Liquid properties, environmental conditions, pipette geometry, and even controller behavior all interact with technique in ways that are not always obvious.

Focusing exclusively on user error can prevent meaningful adjustments elsewhere in the system. A more useful approach is to view volume transfer as a combination of tool design, liquid behavior, and human input. This perspective shifts the goal from eliminating error entirely to managing variability intelligently.

Conclusion

Understanding the design logic and practical nuances of serological pipettes ultimately serves one purpose: improving consistency and confidence in everyday lab work. When researchers know why certain features exist—and where common assumptions fall short—they can focus less on second-guessing their tools and more on their experiments.

With that perspective in mind, GenFollower’s serological pipettes are designed to support reliable, routine liquid handling without unnecessary complexity. The tubes are made from optical-grade polystyrene for clear visibility, with well-defined graduations and negative graduations that allow better control when working close to the upper volume limit. Compatibility with mainstream pipette controllers from brands such as Eppendorf, Brand, Thermo, and others ensures easy integration into existing workflows.

Recent Posts

FAQs: Why Are Your Cryovials/Cryo Boxes Always Causing Trouble?

In our previous article, Cell Cryopreservation: Common Protocols, Thawing Tips, and FAQs, we addressed operational best practices for freezing and thawing cells, along with several technique-related questions frequently encountered in laboratory workflows. While procedural [...]

Cell Cryopreservation: Common Protocols, Thawing Tips, and FAQs

Imagine this scenario: You’ve spent months carefully cultivating a unique cell line or editing a specific gene. The data looks promising, and it’s time to bank these precious samples for future verification. You freeze [...]

Comprehensive Analysis of Lab Automation Workstations: Mainstream Brand Selection Guide

Let’s face it: nobody becomes a scientist because they love pipetting 384-well plates by hand. It is tedious, physically draining, and—worst of all—prone to human error that can quietly ruin weeks of hard work. [...]