Fast, automated sample preparation improves laboratory efficiency while ensuring data reproducibility by reducing human error and sample loss during transfer. These technologies also support green chemistry initiatives by minimizing solvent waste. While modern analytical instruments have reached high levels of automation through advanced computing, sample preparation remains a vital link in the analytical chain. The continuous innovation in sample prep technologies is crucial for overcoming bottlenecks in complex sample analysis and advancing the field of analytical chemistry.

Why is sample preparation so important?

A complete sample analysis process can generally be divided into four steps:

① Sample Collection;

② Sample Preparation;

③ Analytical Determination;

④ Data Processing and Result Reporting.

Among these, sample preparation is the most time-consuming stage, accounting for approximately two-thirds of the total analysis time. While the instrumental analysis of a sample typically takes only a few to tens of minutes, the preceding preparation phase often requires several hours. Therefore, sample preparation is a critical step in the analytical process; the sophistication of the preparation method directly determines the quality and performance of the overall analytical approach. Due to its vital importance, research into sample preparation methods and technologies has garnered widespread attention from analytical chemists.

Classification and Development of Sample Pretreatment Techniques

1. Classification of Sample Pretreatment Techniques

Based on the physical state of the sample, sample preparation technologies are primarily classified into three categories: solid, liquid, and gas sample preparation.

-

Solid Sample Preparation: Technologies mainly include Soxhlet Extraction, Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE), Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE), and Accelerated Solvent Extraction (ASE), among others.

-

Liquid Sample Preparation: Technologies primarily consist of Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE), Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE), Liquid Membrane Extraction (LME), Purge and Trap (P&T), and Liquid-Phase Microextraction (LPME).

-

Gas Sample Preparation: Methods include Solid Sorbent methods and Whole Air Sampling methods.

2. The development of sample pretreatment techniques

Among current sample preparation techniques, classical methods remain the most widely utilized. Their continued dominance is driven by technical refinements, the emergence of novel materials and reagents, and the continuous development of more ergonomic and efficient equipment.

(1)Sample Processing (Comminution): Sophisticated and efficient grinding equipment, such as high-speed and ultra-fine pulverizers, has been developed. These advancements have significantly enhanced processing efficiency and the overall quality of the specimens.

(2)Sample Digestion and Extraction: A comprehensive framework has been established for various digestion systems, including thermal, acid, alkali, molten salt, and enzymatic decomposition, encompassing both dry and wet methodologies. Key hardware innovations include automated high-temperature furnaces, self-controlled oscillators, and ultrasonic extractors.

(3)Separation and Enrichment Methods:

-

Precipitation: Comprehensive systems for inorganic, organic, and co-precipitation have been fully established.

-

Distillation and Volatilization: Sweep co-distillation technology has significantly expanded the application range of distillation. A representative example is the cold vapor atomic absorption (CVAA) mercury analyzer.

-

Solution Extraction and Separation: In inorganic analysis, chelate extraction, ion-association, and acidic phosphorus systems are widely applied for trace element separation. In organic analysis, liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) remains an effective means of purification.

-

Ion Exchange: The introduction of novel ion-exchange resins has extended the application scope of this traditional method.

-

Adsorption: Inorganic analysis utilizes adsorbents such as xanthated cotton; in organic analysis, silica gel, activated carbon, and porous polymers are the most prevalent.

-

Chromatography: Thin-layer chromatography (TLC), extraction chromatography, column chromatography, centrifugal chromatography, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), and capillary chromatography are highly active in their respective fields. The evolution of chromatography represents the primary direction for the future of separation and enrichment technologies.

Research progress in sample pretreatment techniques

1. Miniaturization

With the rapid advancement of terminal detection instrumentation, the required sample volume for analysis has continued to decrease. Consequently, sample preparation systems are evolving toward miniaturization to align with these highly sensitive detection capabilities. This trend toward micro-scale processing was first extensively adopted in the field of medical diagnostics.

2. New methods and technologies

The development of new methods and technologies involves both improvements to traditional methods and the introduction of new principles and techniques. The following sample pretreatment techniques have developed rapidly in recent years:

1) Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE)

A supercritical fluid is a substance at a state between its critical temperature and pressure. The separation principle of SFE leverages the relationship between the fluid’s solubility and its density—specifically, how pressure and temperature influence the dissolving power of the supercritical fluid to perform extraction. It overcomes the drawbacks of traditional Soxhlet extraction, such as being time-consuming, labor-intensive, and having low recovery, poor reproducibility, and high pollution. SFE makes the extraction process faster and simpler while eliminating the hazards of organic solvents to human health and the environment. Furthermore, it can be coupled (hyphenated) with various analytical instruments and is widely applied in pharmaceuticals, food science, chemistry, and environmental monitoring.

2) Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME)

The principle involves coating various cross-linked bonded stationary phases onto a plunger inside a syringe-like device. During operation, the fiber (plunger) is extended and immersed in the crude sample solution, where target analytes are adsorbed onto the coating. The fiber is then retracted and directly inserted into the inlet of a Gas Chromatograph (GC) or Liquid Chromatograph (LC), where the analytes are desorbed for chromatographic analysis. This technology offers advantages such as simple operation, short analysis time, minimal sample volume, and excellent reproducibility. By utilizing GC or HPLC as downstream analytical tools, SPME enables rapid separation and analysis of diverse samples. By controlling various extraction parameters, it achieves high repeatability and accuracy for the determination of trace components.

3) Automated Gel Cleanup (GPC Cleanup)

Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) is a type of liquid chromatography where separation is based on the difference in the molecular volume of solutes in a solution. Automated gel cleanup utilizes this principle to purify samples and has been widely applied in recent years for the separation and purification of biological, environmental, and medicinal samples.

4) Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE)

Developed in the late 1970s, SPE is a sample preparation technique that uses solid adsorbents to adsorb target compounds, separating them from the sample matrix and interfering compounds. The targets are then recovered through elution with a solvent or thermal desorption, achieving separation and enrichment. This technology features high recovery, high enrichment factors, low organic solvent consumption, and rapid operation. It is easily automated and can be coupled with other analytical instruments. In many scenarios, SPE has replaced traditional Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE) as the preferred method for aqueous samples, such as in U.S. EPA methods for determining pesticide levels in water.

SPE Column

5) Liquid-Phase Microextraction (LPME)

The principle of LPME is based on the differential solubility and distribution ratios (partition coefficients) of analytes between two immiscible solvents. This technology integrates extraction, purification, concentration, and pre-separation into a single step. It offers high extraction efficiency, low solvent consumption, speed, and high sensitivity, making it an environmentally friendly extraction method.

6) Purge and Trap (P&T)

Purge and Trap (P&T) leverages the volatility of analytes. It involves purging the sample with a carrier gas to extract volatile components, which are then collected using cryogenic trapping or sorbent trapping before being introduced into a chromatograph for analysis. P&T technology offers advantages such as rapid processing, high accuracy, extreme sensitivity, and high collection efficiency. It demonstrates vast application prospects in the sample preparation of food, beverages, vegetables, and pharmaceuticals.

Purge and Trap Concentrator

7) Membrane Separation Technology

Membrane separation uses a selectively permeable membrane as the separation medium. By applying a driving force—such as a pressure differential or concentration gradient—across the membrane, specific components are allowed to pass through while others are retained. Typically, low-molecular-weight solutes pass through the membrane while macromolecules are intercepted, achieving separation and purification based on molecular weight. Operating primarily under pressure, the process is nearly instantaneous, offering a compact footprint, simple device structure, and ease of automated operation. This technology can replace traditional methods like centrifugation, sedimentation, evaporation, and adsorption, significantly improving efficiency and reducing operational costs.

8) Thermal Desorption (TD)

Thermal Desorption involves placing solid, liquid, or gas samples—or sorbent tubes containing adsorbed analytes—into a thermal desorption unit. As the temperature rises, volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds (VOCs/SVOCs) are released and carried by an inert carrier gas into a GC or GC-MS for analysis. This technique is characterized by high sensitivity and minimal environmental impact. When hyphenated with gas chromatography or mass spectrometry, it becomes a powerful tool for analyzing complex samples across a wide range of applications.

9) Microwave Digestion

In a microwave magnetic field, the polar molecules of the sample undergo rapid rotation and directional alignment, generating internal vibration and heat. Digestion under high temperature and pressure activates chemical substances and significantly enhances the oxidizing power of reagents. This process disrupts the sample surface, continuously exposing new surfaces to the reagents and accelerating the digestion. Microwave digestion is a highly efficient, time-saving modern preparation technique, universally utilized for sample pretreatment in atomic spectroscopy (such as ICP-OES and ICP-MS).

3. Online Techniques

Online techniques involve the direct integration of sample preparation processes with terminal detection systems to achieve streamlined automation. The prevailing trend is the seamless coupling of these two stages. This integration not only alleviates labor intensity and optimizes human resources but, more importantly, effectively prevents unavoidable errors stemming from human variability in manual operations. Ultimately, this seamless integration significantly improves the sensitivity, accuracy, and reproducibility of analytical measurements.

How to Choose Measurement Conditions for AAS

The process generally comprises five key components: the selection of the analytical line, followed by the optimization of slit width, the determination of hollow cathode lamp operating current, the selection of atomization conditions, and finally, the adjustment of sample volume.

1. Analytical Line Selection

The resonance absorption line is typically selected as the analytical line. When determining high-concentration elements, a non-resonance absorption line with lower sensitivity may be chosen instead. Since the resonance lines for elements such as As and Se are located in the far-ultraviolet region below 200 nm, where flame components exhibit significant absorption, these lines are unsuitable for Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (FAAS).

2. Slit Width Selection

Slit width affects the spectral bandwidth and the energy received by the detector. In atomic absorption spectrometry, the probability of spectral overlap interference is low, allowing for the use of relatively wide slits. By adjusting the slit width and measuring the resulting absorbance, it can be observed that absorbance decreases immediately if other spectral lines or non-absorption light enter the spectral bandwidth. The optimal slit width is defined as the maximum width that does not cause a decrease in absorbance.

3. Hollow Cathode Lamp (HCL) Operating Current Selection

Hollow cathode lamps generally require 10–30 minutes of preheating to achieve stable output. If the lamp current is too low, the discharge becomes unstable, resulting in erratic spectral output and low intensity. Conversely, excessive current causes emission line broadening, leading to reduced sensitivity, curvature of the calibration curve, and shortened lamp life. The general principle is to use the lowest possible operating current that ensures a sufficiently strong and stable output. Typically, one-half to two-thirds of the maximum current specified on the lamp is used, though the most suitable operating current for a specific analysis should be determined experimentally.

4. Selection of Atomization Conditions

1) Flame Type and Characteristics

In flame atomization, the type and characteristics of the flame are the primary factors affecting atomization efficiency. An air-acetylene flame is used for low-to-medium temperature elements, while a nitrous oxide-acetylene high-temperature flame is preferred for high-temperature elements. For elements with analytical lines in the short-wave region (below 200 nm), an air-hydrogen flame is suitable. For a given flame type, a slightly fuel-rich flame (where the fuel flow exceeds stoichiometric proportions) is generally advantageous. For elements with relatively unstable oxides, such as Cu, Mg, Fe, Co, and Ni, a stoichiometric flame (where the ratio of fuel to oxidant is close to their chemical reaction ratio) or a lean flame (fuel-lean) may also be used. To obtain a flame with the desired characteristics, the ratio of fuel to oxidant must be adjusted.

2) Selection of Burner Height

Within the flame zone, the spatial distribution of free atoms is non-uniform and varies with flame conditions. Therefore, the burner height should be adjusted so that the light beam from the hollow cathode lamp passes through the region of the flame with the highest concentration of free atoms to achieve maximum sensitivity.

3) Selection of Temperature Programming Conditions

In graphite furnace atomization, it is crucial to reasonably select the temperature and duration for drying, ashing, atomization, and burnout (cleaning). Drying should be conducted at a temperature slightly below the solvent’s boiling point to prevent splashing. The purpose of ashing is to remove the matrix and extraneous components; the highest possible ashing temperature should be used, provided there is no loss of the target element. The principle for selecting the atomization temperature is to use the lowest temperature that achieves the maximum absorption signal. The atomization time should be sufficient to ensure complete atomization. During the atomization stage, the flow of protective gas is stopped to extend the average residence time of free atoms within the graphite tube. The purpose of burnout is to eliminate memory effects caused by residues; therefore, the burnout temperature should be higher than the atomization temperature.

5. Sample Volume Selection

If the sample volume is too small, the absorption signal will be too weak for accurate measurement. If it is too large, it may cause a cooling effect on the flame in flame atomization or increase the difficulty of residue removal in graphite furnace atomization. In practice, the relationship between absorbance and sample volume should be measured; the volume that yields the most satisfactory absorbance is the optimal sample volume to be selected.

Recent Posts

Knowledge Sharing: 9 new technologies for sample preparation

Fast, automated sample preparation improves laboratory efficiency while ensuring data reproducibility by reducing human error and sample loss during transfer. These technologies also support green chemistry initiatives by minimizing solvent waste. While modern analytical [...]

Common Contamination Source Issues in Microbiology Labs

In day-to-day microbiology work, contamination is often recognized not through a single dramatic failure, but through recurring, difficult-to-explain inconsistencies. Plates that were clean in previous runs begin to show unexpected colonies, negative controls occasionally fail, [...]

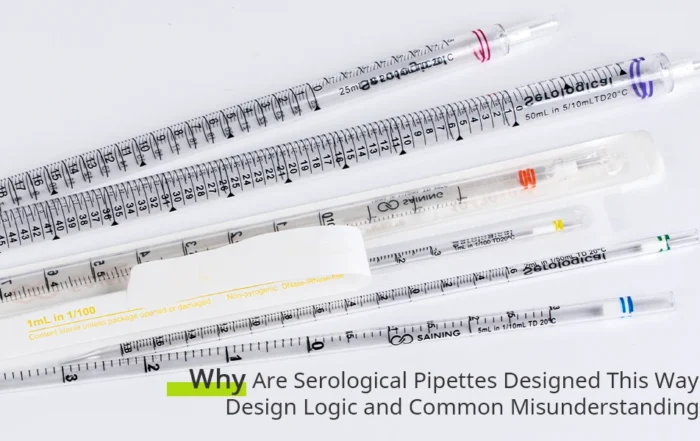

Why Are Serological Pipettes Designed This Way? Design Logic and Common Misunderstandings

Serological pipettes are part of everyday life in many laboratories. Whether transferring culture media, handling large liquid volumes, or supporting routine cell culture work, they are often picked up almost without thinking. Their shape, [...]